St. Anthony on Staying Where You Are

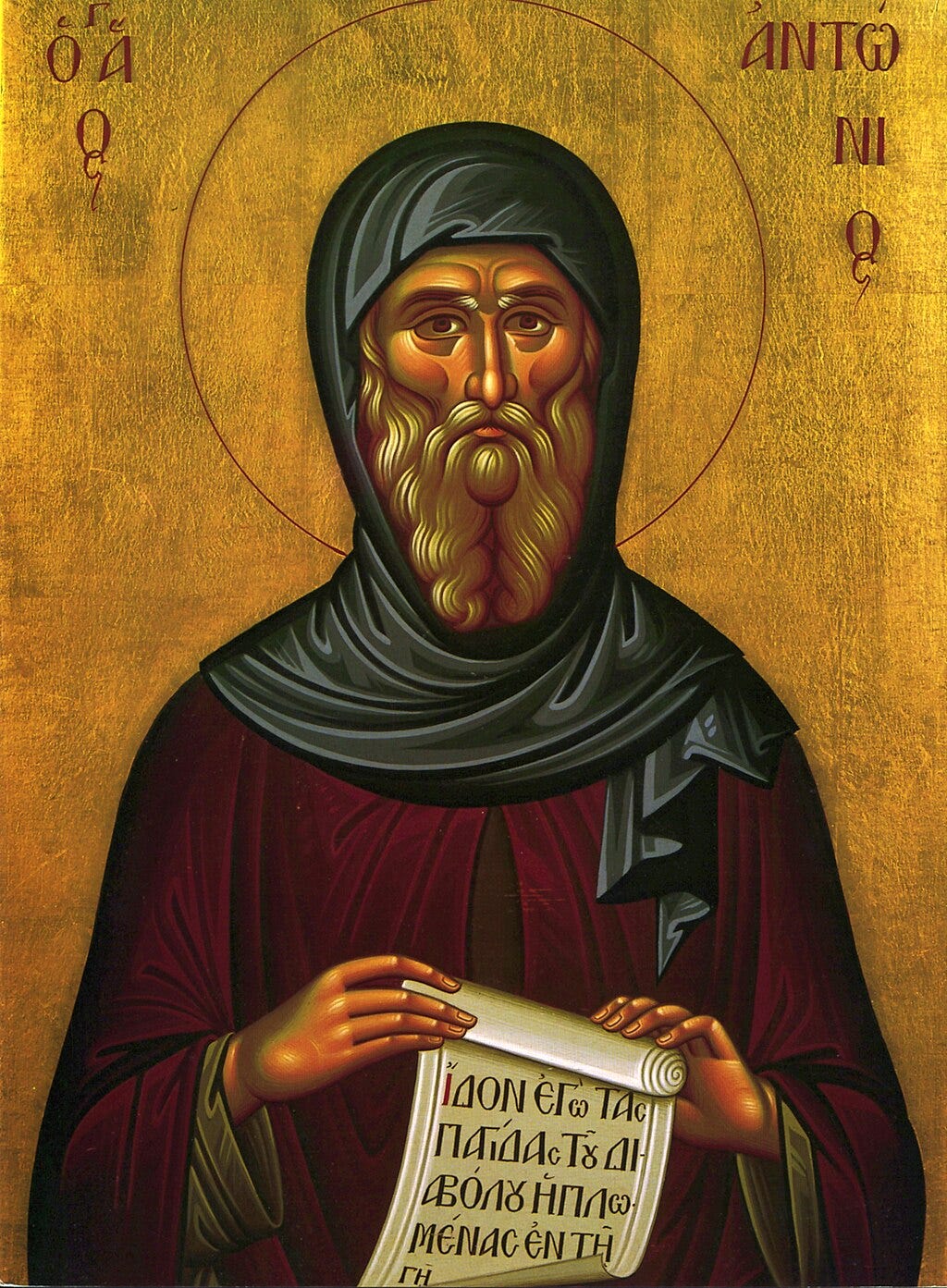

When someone asked St. Anthony, an early Church Father and great monastic, how best to please God, the saint had some pretty interesting things to say.

“Pay attention to what I tell you,” the old man said first. “Whoever you may be, always have God before your eyes.”

“Whatever you do, do it according to the testimony of the holy Scriptures.”

And last and perhaps most interestingly:

“In whatever place you live, do not easily leave it. Keep these three precepts, and you will be saved.”1

I think about St. Anthony’s response, catalogued neatly and almost obscurely in a single paragraph in The Sayings of the Desert Fathers, as I bend down early this morning to pull last summer’s weeds from a neglected bed, the thorny heads of sandbur catching and sticking against my wrists.

It is cold here today. And dry. It is almost always dry here along the llano estacado, the lonely, desert sweep of West Texas where we live. The dryness, like this work, is a drudgery.

I pull the thorns from my skin with irritation, curse when the heads cling to my gloves when I fling them into the trashcan. The ground in this eight-foot patch along the fence is as hard as stone, and yet, these weeds are what flourish here? Where I pluck a hook-like needle from my skin, a small circle of red pulses. The discomfort only adds to my irritation.

St. Anthony’s admonition - that third one to stay where you are, don’t easily leave it - also irritates this morning.

I can swallow the first two pieces of St. Anthony’s advice because they involve the wholeness of one’s life. I can swallow always having God before me and referring to the Scriptures in whatever I do. But it’s that third precept I pick at – the one that is limited by time and location, where you live now – that pricks like a thorn. Sometimes, I want to leave this place. Live anywhere the is normal color is green and not brown, where the seasons are gentler. Where it rains.

And where, perhaps, the thorns, aren’t so brutal.

Why does where I live (and whether or not I leave it), I think as I unsuccessfully swipe at another clump of weeds, have anything to do with pleasing God?

The answer, it turns out, is found deep in another desert 1,700 years ago.

***

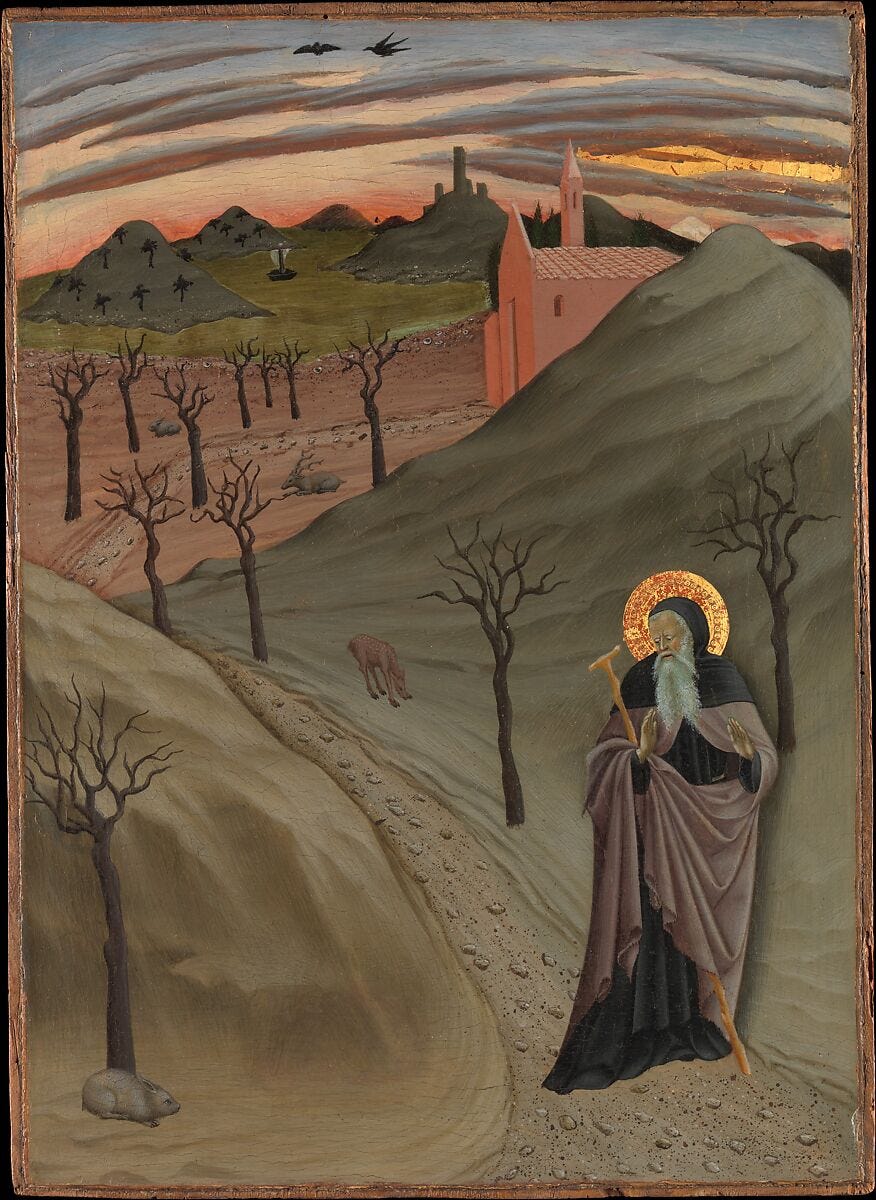

St. Anthony (or Antony) was born around 251 in Egypt to parents who were Christians. Orphaned in his late teens, he was moved, tradition teaches, by Christ’s last response to the rich young man in Matthew’s gospel, who asked the Savior which commandments he should keep in order to have eternal life. Christ listed off a heavy six (murder, adultery, stealing, bearing false witness, honoring your mother and father, and loving your neighbor), to which the young man replied, “All these things I have kept from my youth. What do I still lack?”

Christ knew all this already, of course. The rich young man was very good at keeping the law, and his heart was very good at keeping his riches. So Christ responded with the kicker, the medicine this particular young man needed:

If you want to be perfect, go, sell what you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; and come, follow Me (Matthew 19:16, 18, 20-21, NKJV).

Unlike the young man, who walked away sorrowfully from this unbearable advice because he was very rich, St. Anthony embraced Christ’s suggestion with conviction. He sold all his belongings and donated his inheritance – including “three hundred fertile and very beautiful arourae [acres of farmland]” – to the poor and townspeople of his village, reserving only a small portion for the well-being of his younger sister, for whom he was responsible.2 After this, he began an ascetic practice, first by studying and laboring just outside his village.

“There were not yet many monasteries in Egypt,” St. Athanasius the Great, Anthony’s contemporary, friend, and first biographer wrote about St. Anthony, “and no monk knew at all the great desert, but each of those wishing to give attention to his life disciplined himself in isolation, not far from his own village.”

St. Athanasius began observing St. Anthony sometime in St. Athanasius’s youth and was a witness to the saint’s acts. Not long after St. Anthony’s death and at the pressing of brethren, he wrote The Life of Antony, “dispatched to the monks abroad.”3 Monasticism was beginning to take a strong foothold, and people wanted guidance on how to pursue the path.

“You have entered on a fine contest with the monks in Egypt,” St. Athanasius begins his introduction to the monks too far away to visit in person:

For by now you have monasteries, and the name of the monks carries public weight … may God bring your requests to fulfillment.

Eventually, his biography continues, St. Anthony left the vicinity of his village altogether to occupy an abandoned fortress, “empty so long that reptiles filled it,” deep in the Eastern Desert of Egypt to pursue an even deeper ascetic practice.

It was a desolate, monochromatic place to choose a home. The Eastern Desert of Egypt, a sandy highland covering almost 86,000 square miles between the Nile and the Red Sea, offered little in terms of comfort or companionship, which was the point. Long stretches of hot, golden earth were punctuated only with the blues of an overhead sky or occasional wadi, a dry channel that filled with water when rare rains arrived.

Most of the time, they filled only with the feet of travelers on routes out of the desert.

It was here, in a setting that could only exacerbate the internal and external spiritual struggles the saint endured, that St. Anthony lived for “nearly twenty years … pursuing the ascetic life by himself, not venturing out and only occasionally being seen by anyone.”

Those twenty years were up when a crowd of people, desperate to emulate the saint, gathered outside his fortress while “some of his friends,” physically ripped his door off its hinges. St. Athanasius continues:

Antony came forth as though from some shrine. This was the first time he appeared from the fortress … And when [the crowds] beheld him, they were amazed to see that his body had maintained its former condition … [he] was just as they had known him prior to his withdrawal.4

Only, St. Anthony was radically different.

Despite years of restriction and spiritual battle, he was peaceful, neither surprised nor emboldened by the crowds gathered outside his door. “He maintained utter equilibrium,” St. Athanasius reflected, “like one guided by reason.”

Nearly twenty years in the most inhospitable place of solitary fasting, prayer, struggle, and endlessly pursuing God – his work toward theosis – had transformed him. His miracles began almost immediately, and “when he spoke” to the people gathered at his fortress – consoling, encouraging, and “urging everyone to prefer nothing in the world above the love of Christ,” - in the process “he persuaded many to take up the solitary life.” As a result,

from then on, there were monasteries in the mountains, and the desert was made a city by monks.

With all of this, of course, meant the flight of St. Anthony’s own solitude. He became, in a sense, a monastic celebrity. He was constantly sought for wisdom, asked for help. Even Satan lamented, in one astonishing interaction with the saint recorded by St. Athanasius, the loss of his territory created by the growing Faith:

There are Christians everywhere, and even the desert has filled with monks.5

St. Anthony embraced and eventually defined a monastic practice that fulfilled a hungry longing to engage deeper with God. This practice, for some, was also an answer to the crushing persecution of Christians that occurred in the Roman Empire between the first and fourth centuries.

One of the most severe persecutions, known as the Diocletianic Persecution, occurred during St. Anthony’s time. Maximium governed Egypt with Diocletian and enacted both empiric and local persecutions against Christians, ranging in everything from mutilation for failing to offer sacrifices to the gods to expulsion of Christians from their homes and cities.

Naturally, a flight into the desert by the faithful ensued. Perhaps this is why the saint advised those wishing to leave, flee, or abandon their situation (including, perhaps, spouses and families) first pause and consider what they would be abandoning. Marriages and children were not to be abandoned in favor of monasticism; this was against the Church’s teaching and sacraments and still is.

The irony, of course, is that St. Anthony left his first home, including a young sister to care for, farmland to cultivate, and an inheritance and occupation to manage. These, at first glance, seem the responsibilities that modern readers might loathe to abandon or easily condemn St. Anthony for leaving behind. In other words, he had plenty to consider sacrificing.

However, he wasn’t married, and he didn’t have children. He provided for his younger sister and ensured that she was left in the care of nuns, likely at a nearby convent, and gave everything else to everyone else. Unlike the rich young man from the gospels, St. Anthony did not go away sorrowfully. But he did struggle. Intensely.

For the rest of his life until his death in 356 near the Red Sea, St. Anthony battled against demons, his passions, and himself: all that separated him from his love of God. “This is the great work of a man,” St. Anthony said to Abba Peomen. “Always to take the blame for his own sins before God and to expect temptation to his last breath.”6

***

In whatever place you live, do not easily leave it.

I am no St. Anthony. But his story of place, I think, lingers with me as much as his story of sainthood.

He was not the first “Desert Dweller,” for he imitated what St. John the Baptist accomplished in his own desert living: enduring a labored existence while heralding the coming Christ. And there were other monks already etching out a spiritual practice in the desert before St. Anthony’s time, too.

But I am moved by how he embraced the desert for what it could offer, instead of, perhaps, focusing on what it lacked. Leaving his beautiful farmland and village by degrees meant leaving behind cultivation, beauty, means, and the certainty of other people and their presence.

The desert meant entering into wilderness, lack, and the terror that comes with facing oneself, alone.

But the desert ultimately meant entering into the certainty of Christ and His Presence. Could a life in his village, surrounded by his friends and family, beautiful acreage, and comforts have provided the setting St. Anthony needed to pursue God so diligently? I don’t think so. St. Anthony didn’t think so, either.

***

So here I am, in West Texas, to some the most lonely, inhospitable stretch of earth in the state. Freezing, windy, and dry; scorching, windy, and dry: these seem our seasons.

Some people curse living here, and there are thousands of comments made everyday - out loud, online, and sadly, even in person to me - about what an ugly wasteland West Texas is. Like those traversing the empty wadis out of St. Anthony's desert, many leave this place as soon as they are able.

I have dreamed of leaving. And I have.

And yet …

West Texas is the place that by both chance and choice I have made my home. It is where I live out my daily life as a Christian, wife, mother, and servant. Although I have had opportunities – and many, many dreams – to flee, it is also the place I have not easily left.

I learned long ago that the Christian life is not easy, no matter where one lives. I could leave this place in favor of a thousand different settings, most with a better view from my window. But I have also learned the desert of my back yard is always going to mirror the desert of my spiritual life if I don’t change my interaction with both.

All of this, of course, points back to a subtle point St. Anthony made with his advice.

“What must one do in order to please God?” he was asked.

It’s not necessarily a bad question, for even God the Father says, “This is My Beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased” (Matthew 3:17, NKJV).

But the saint, as so many of our Church Fathers were wont to do when addressed with questions like this, replied instead with a commentary on salvation. What can we do to be saved?

And it’s salvation, which includes the whole engagement of one’s entire life with God, our relationship to Him, what we do with that love, that is experienced in the life we have now: the stuff of our ordinary, dusty, daily lives that we choose to face and endure, right where we are, however long where we are lasts.

St. Anthony wasn’t against all people leaving the city for the desert or the desert for the city, but he advised careful discernment (prayer, guidance) in any decision to pursue something that might seem more exciting or fulfilling. Will this new setting ultimately bring one closer to God and His will? Or is where we presently struggle something God can use to bring us closer to Him?

“Ought I to go?” St. Anthony asked Abba Paul, his disciple, when a letter arrived from Emperor Constantius inviting St. Anthony to Constantinople.

“If you go,” his disciple replied, “you will be called Anthony; but if you stay here, you will be called Abba Anthony.”7

For most of St. Anthony’s life, the desert remained his here.

***

I kick at a dirt clod and think about all of this, again, as a cerulean and magenta sunrise slices through the tops of the vitex. A last line of Canada geese, holdovers from the winter, wave overhead like a ribbon in the wind. Yes, it will be dry again today. If I can clear these weeds, soak the ground, the purple-tipped alliums won’t need as much help breaking through the hard earth. I can trim back the wilted iris leaves, reveal their footed rhizomes to the baking sun.

I know no one is going to rip the doors off my house today and see me emerge, illuminated, but I will do what I can in the desert I have chosen. I will take out the trash, finish folding the towels, put the soup in the pot before I pick up my little boy from school.

St. Anthony will be with me as I bend and rake, fold and comfort, and West Texas in all its scorching and lonely beauty will offer me its golden, monochromatic space for contemplation. It will offer me God.

I will not easily leave it.

***

“Anthony the Great,” in Benedicta Ward (trans.), The Sayings of the Desert Fathers (Trappist, KY: Cistercian Publications, 1975), p. 2.

Athanasius, in Robert C. Gregg (trans.), The Life of Antony (New York, NY: HarperOne, 2006), p. 6.

Ibid, p. 3.

Ibid, p. 17-18.

Ibid, p. 40.

Ibid, p. 2.

Ward, p. 8.