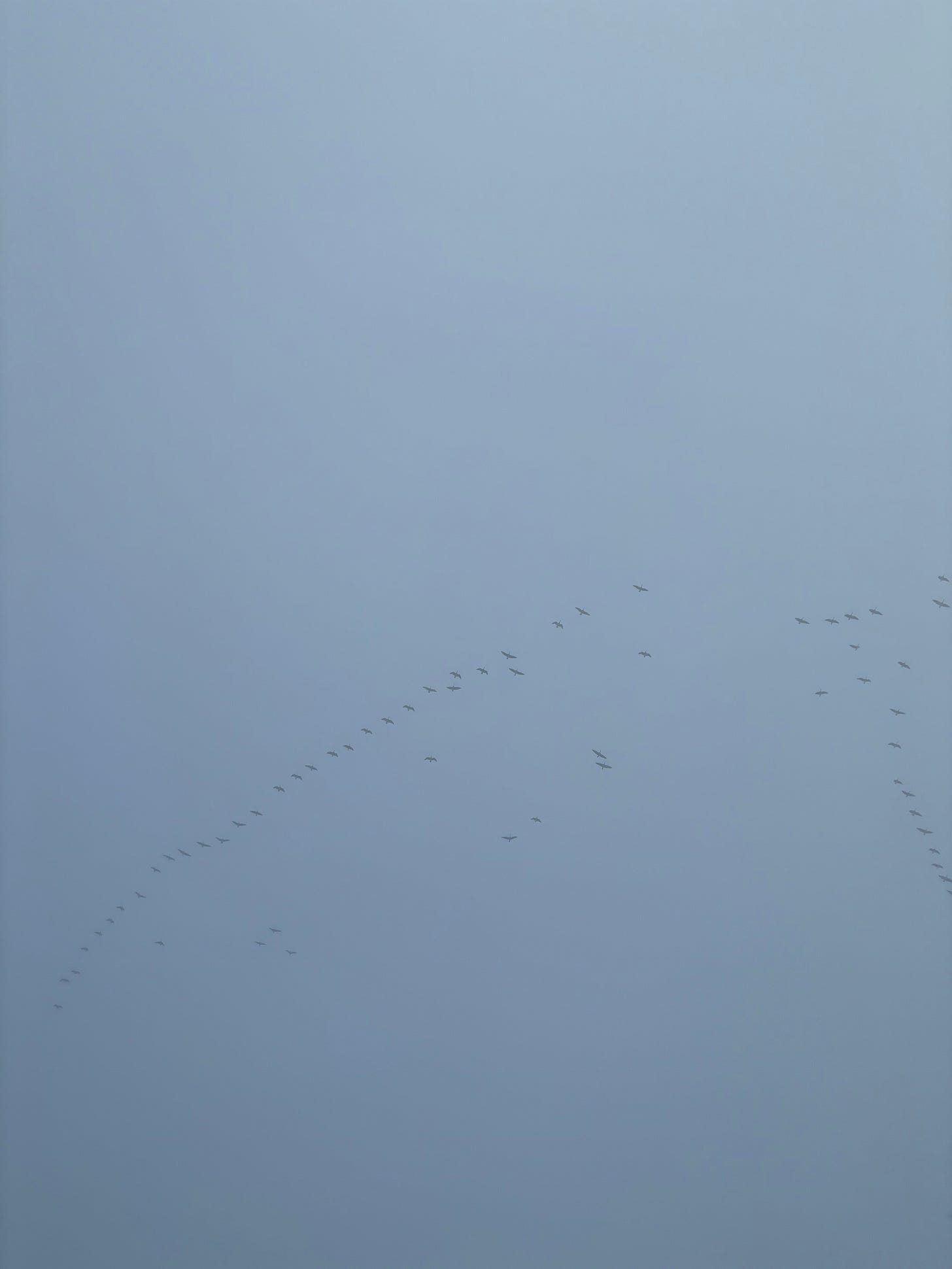

January – the first chapter of the year – is closed. But the Canada geese are still here.

Nothing makes me as happy as hearing them squonking above me, their tenor shouts encouraging each other as they leave the city and vee out to the fields to feed. “Thrice glad ye make us with your wild hosannas,” Richard Hoe Barrows wrote in “The Passing of the Wild Geese,” and their calls are indeed hallelujahs.

If I’m up early enough – and sometimes if the weather is particularly cold or rainy, delaying their morning flight – I will catch their wild and triumphant departure over my head as we load up for school. It makes me as giddy as a child. “Look!” I tell my son in my arms, pointing at the sky. He looks up, squinting.

“Do you hear them?” I say. “Do you hear the geese?”

“Geeth,” he repeats, not quite conquering the word at three. And for the rest of the day, he’ll point to every bird perched in a tree or electric line we pass. “Geeth, Mommy, geeth!”

***

We have the good fortune of living near a playa lake that’s a temporary winter home to thousands of migrating Canada geese. Situated in the middle of a park about half-mile through the neighborhood, the playa is a natural depression that fills with only a few feet of water with sporadic rains and runoff. Although it is shallow, its thick clay bottom keeps the water in the center from soaking into the ground too quickly, while the water at its edges slowly recharges our most precious groundwater resource, the Ogallala Aquifer.

While temperatures are mild, like here in the winter, the playa only completely evaporates between rains, but when the brutal heat of summer hits, it’s not unusual to walk across a bed of dried earth on the bottom, crazed like an old dish accidentally run through the dishwasher.

On the way to drop off my little one at school, we pass a city dump truck with the slogan Keep our playas clean! plastered across its side. If you live in West Texas, you likely take the playa for granted, assuming the still, murky water useless since you can’t swim it and wouldn’t dare eat any fish you’d catch in it. But the playa is so much more, as vital to our ecosystem as the air we breathe. These still, silver pools reflecting like coins are life’s precious currency for birds that make their permanent and temporary homes here.

And it is during the three months or so of the year – when the trees turn from green to pale gray and our exhalations become visible in the cold air – that I revel in the Canada geese who’ve come to stay.

This morning, I stop and take a photo of them on my walk and wonder how anybody couldn’t adore them. A flock moves slowly through the park grass, gone yellow with the frost. These beautiful birds are mostly herbivores, favoring sedges, stems, seeds, and grains for their morning breakfast. Some lift their heads high at my approach, the delicate curve of their beaks making them look like a punctuation mark or ancient letter of a lost alphabet. When I coo some ridiculous compliment to them, one turns his head toward me, the characteristic swath of white feather smeared like stage makeup across his cheek and chin.

Indeed, these birds could be actors; they move with grace and not a little bit of drama through the field, lifting their leathery black legs in exaggerated slowness. Watching a Canada goose in motion, one cannot help but appreciate the body. All the bird’s weight and equilibrium are carried in that elongated rump that shifts slowly back and forth in a black-and-brown wave as the goose plods carefully on two webbed feet made more for water or air than ground. Almost 25,000 downy feathers encase each goose, all of which are shed and replaced each year. To observe a Canada goose like this is to want to hug it; you can imagine how heavy that thick, feathery body must feel in your arms.

But I can’t hug one, and as friendly as I am, the geese are naturally much more wary. The flock moves diagonally away from me at a coordinated pace, the onyx shine of one of almost every pair of eyes watching me as they retreat. If I were to charge them (which I would never do), or if the dog I see on a leash across the street were to break free toward the crowd of birds, I’d see that slow daintiness disappear, and they would explode into an airborne powerhouse of muscle and lift.

Thankfully, none of that happens. I stand for a few minutes in the quiet until they take their exit, bowing as they careen through the dried grass, the fog lowering a blue-gray curtain around them.

***

Search for mention of geese or goose in the Scriptures, and one doesn’t come up with much. When these words are mentioned in translation, its usually in a list of possessions, payments, or prosperity. Take Solomon, for example, whose “provisions for one day” included “ten fatted oxen, twenty oxen from the pastures, and one hundred sheep, besides deer, gazelles, roebucks, and fatted fowl” (1 Kings 4:22-23, NKJV). These provisions, of course, would be for eating and other uses, like plucking, rendering, and stuffing.

But the Psalms provide lovely references to “flying fowl,” which would have included, of course, geese. My favorite is Psalm 148, a cosmic hymn of praise read in the Orthodox Church during every matins (orthros) service. After nine specific “praises,” the psalmist lists a tenth, to be exclaimed by everything “from the earth”:

“Praise the Lord from the earth,

You great sea creatures and all the depths;

Fire and hail, snow and clouds;

Stormy wind, fulfilling His word;

Mountains and all hills;

Fruitful trees and all cedars;

Beasts and all cattle;

Creeping things and flying fowl …” (Psalm 148:7-10, NKJV).

The back-and-forth of opposing items (hot fire and freezing hail, tall mountains and humble hills, wild beasts of the earth and cultivated cattle, ground-hugging creatures and bird flying high in the air) create the swish-swash cadence that reminds me of their gait through the grass. The lines in English are lulling in their lists but astonishing in their greater meaning: Everything in creation, domestic and wild alike, is commanded to “praise the name of the Lord, / For He commanded and they were created” (Psalm 148:5, NKJV).

And that only the beginning of the psalm’s praise!

I do not think it takes much for the Canada goose to praise the Lord, and I don’t think they need the psalmist to tell them to do it. I like to imagine, in the constant ascent and descent that is their lives, that praising their Creator would come quite naturally to them. Who knows? Maybe all the squonking and honking I hear above me in the early morning and later darkness when they return to their waters are actually songs of joy as much as songs of work.

I wonder this because sometimes when I step outside at just the right moment, the pinkish light of the sunrise reflects off their bellies and makes them shine. Then they become not just birds, but black-and-golden orbs, living jewels that fly over our houses, over our cars, over the rust and cold and ordinary of our days.

And I think: Am I the only one who catches them in that exact moment? Surely I can’t be.

They are quite honestly raucous while they live with us. For weeks I’ll find geese feathers and bright-green droppings all over the park on my walks. Like college partygoers, they are social, loud, and leave a bit of a mess when it’s time to go get food. They visit as ubiquitous guests, noisily announcing all their comings and goings.

But if I’m not careful and don’t listen for them, search for them in the skies, they begin to bleed into the background of winter days.

Mary Oliver wrote in her oft-quoted poem, “The Wild Geese,” (read by the poet’s own voice here):

“Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile, the world goes on …

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean, blue air,

Are heading home again.”

I think about all the busy commuters on their gray roads, local and passing through, who might not notice the geese. Or more sadly: people who are entombed by despair, difficulties, or hardness who never notice them at all, don’t recognize the eerie quiet when one February day, they’ve all lifted for the last time. “Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,” Oliver’s poem ends, “the world offers itself to your imagination, / calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting - / over and over announcing your place / in the family of things.”

Wendell Berry, a contemporary, says it in a different way, in “The Wild Geese:”

“Geese appear high over us,

pass, and the sky closes. Abandon,

as in love or sleep, holds

them to their way, clear,

in the ancient faith: what we need

is here. And we pray, not

for new earth or heaven, but to be

quiet in heart, and in eye

clear. What we need is here.”

I read this as delightfully anti-gnostic. What we need is here. While our world spins below, another one spins above. But if we take the time to look and notice, we’ll hear the call about where we belong in it all, and the reminder that what we need is already around us, if only we attune ourselves to it. God has already provided all we need for recognizing His presence, right here and now. It is as simple, I think, as noticing the geese and our relationship to them.

No, I think, rereading Psalm 148. The praise is definitely mine to remember.

***

Interestingly, February 1 is the feast day of St. Tryphon of Phrygia. Born in the ancient Greek village of Lampsacus (which is near today’s Lapseki, Turkey), he was filled with a “great grace of God” from childhood, “such that he was able to cure illnesses that afflicted people and livestock.”[1] One interesting and lovely detail mentioned over and over again in every summary I read of him is that he tended geese as a child.

It’s such an ordinary detail of his life. Who wouldn’t have tended some animal in those days? But it hits me as very tender. No doubt the geese he cared for would have had their protector imprinted upon them with the first crack of the egg; and no doubt he would have felt a keen companionship with the fowl that was also sustenance. I think of my sweet little boy’s geeth and how sometimes if we’re walking at the park and he sees them, he puts out his arms, a gesture I know that means he wants to hug them.

St. Tryphon was martyred at a very young age (seventeen, by some accounts) around 250 AD in Nicea during the persecutions of Decius, and tradition teaches that although the people there wanted to bury his body buried in their cemetery, he appeared to them in a vision, asking to be buried in his home village of Lampsacus, where he had tended his geese.

He is depicted in different ways in his iconography: sometimes on horseback holding a merlin (tied to a legend of his intercessions), other times with a cross and hook knife, as he is also a patron saint of winegrowers. But my favorite icons of him are any that include his beloved geese swimming in a blue or silver pool in the foreground.

He loved those geese, and in a way, they returned to him, forever written with him in colors of earth and water.

***

So I remember this afternoon that soon one morning I will go outside, and I will look up and see an empty blue sky. The geese will have left.

They won’t announce their leaving. They will simply take flight one day and begin their long travels north again, away from the playas and the slowly-warming soil.

Away from the yellow grass and a middle-aged woman with a little boy in her arms.

On that day, I know I will think a little ruefully about the long, hot months before they return again and how much I will miss their presence. And I’ll wonder with a jolt: Who will my little boy be when they come back? He is growing so fast. Will he remember their honking in the early mornings before school, his mother’s exuberance, mistaking every grackle and dove shadowed on the lines as geese?

I don’t know. But before I can ponder all this too long, the back door swings open. A little boy, barefoot and covered in sand, with one pant leg hitched up to the knee, shouts:

“Geeth, Mommy, in the sky! I saw the geeth!”

[1] Saint Nikolai of Ohrid and Zhicha, “The Holy Martyr Tryphon of Campsada, near Apamea in Syria,” in Fr. T. Timothy Tepsić (transl.), The Prologue of Ohrid: Lives of Saints, Hymns, Reflections and Homilies for Every Day of the Year (Alhambra, CA: Sebastian Press, 2017), p. 135.

I enjoyed this so much!